Claim

During the summer there are about 4 million pheasants that breed in Great Britain. The estimated population, including those that will come from breeding, is about 1/4 (25%) to 1/5 (20%) of the total mass of breeding birds in the UK. At the beginning of the shooting season, after the release of about 47 million pheasants, the biomass comprises one and a half to two times the total biomass of all of the birds in the UK.

What the science says

Mostly correct.

The pheasant population varies enormously throughout the year, peaking at 50 million birds just after the releases in late summer, and falling to 4.6 million breeding birds in around May. At this time, before the year’s pheasants are released on shoots, pheasants contribute 20% of the total biomass of breeding birds in the UK, which is at the low end of the estimate in the claim.

In September, just before the beginning of the shooting season, total pheasant biomass is about 1.6-1.7 times the total biomass of the British breeding bird population estimate for spring. In September, pheasant biomass is at its highest point of the year while in the spring the biomass of the UK resident breeding bird population is at its lowest, but we do not know what it rises to. The value of this comparison is discussed.

Based on

The underlying source that 4 million pheasants make up 1/4 to 1/5 to of the total biomass of breeding birds in spring stated in this response is likely to be Blackburn and Gaston’s 2018 paper ‘Abundance, biomass and energy use of native and alien breeding birds in Britain’1, with adjustments to provide more up-to-date figures. The figure of 47 million pheasants released per year comes from a paper by Nicholas Aebischer published in 20192.

What the Science says – the fuller picture

To understand these numbers more fully, we need to appreciate and separate the times of year at which comparisons are made. The number of pheasants present in the countryside varies enormously throughout the seasons. This is because they are all released in mid- to late summer, and then numbers steadily decline until more are released the following summer. There are various reasons for this decline, the most important being predation and shooting during the winter shooting season.

There are also truly wild pheasants breeding in parts of Britain, but these populations are small in comparison to the releases. They are also impossible to quantify separately from those that are released, so this piece concentrates on released birds only.

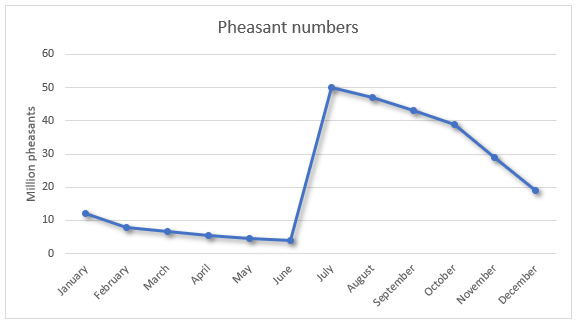

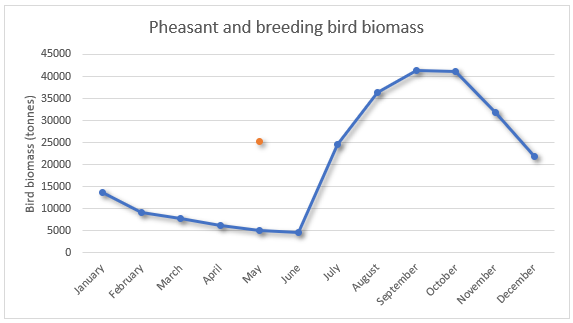

We have used the data that is available to produce the most up-to-date estimates both for numbers throughout the year and the corresponding biomass. Two graphs (figures 1 and 2) summarise our findings. To track the number of released pheasants, there are reasonably good numbers at certain times during the year, but we also need to make some assumptions and approximations to fill the gaps at other times. We have explained how we have done this.

Biomass is the mass of living organisms in a defined area at a given time. To estimate pheasant biomass, we need an average figure for pheasant weight as well as knowing the population size. The most recent published research on pheasant biomass in the UK is from a paper in 20181, which uses values from the population estimates of British breeding birds published by scientists from the British Trust for Ornithology and elsewhere3, along with published body mass data4. That paper used a figure of 0.85kg for the mean body mass of pheasants. Other sources estimate average weight of a pheasant to be 1.15kg5, which we will use in our calculations. When calculating biomass throughout the year it is important to remember that pheasants are not fully grown when released, and would typically weigh around 0.45kg5.

Late Summer (pheasant release) to the start of shooting season

Numbers

The total number of pheasants released in the late summer in the UK was around 47 million in 2016, up from 44 million in 20122. We also need to remember the remaining population of pheasants from the previous year’s release. After the new release we estimate it to be about 3 million (explained below) and it will continue to decline. This gives an estimated maximum total of 50 million released pheasants. Although some sources look at Britain and others use the whole of the UK as their study areas, the figures will be similar.

Biomass

Just after release, 47 of these 50 million pheasants are young birds weighing around 0.45 kg and 3 million are adults weighing about 1.15kg. This provides a total biomass of 24,600 tonnes. This is the point shown in figure 2 for July.

The released pheasants grow quickly, and if the population stayed at 50 million until October, the total pheasant biomass would exceed 50,000 tonnes. However, this number is not correct as the number of pheasants falls steadily after they are released. Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust (GWCT) radio-tracking studies suggest that around 25% of the released birds die before shooting begins in October/November6,7, most of them predated by foxes.

Using these adjustments, the released pheasant population is about 39 million (including 2 million from the previous year) at the start of the shooting season in October. Birds are almost fully grown by then, and assumed to be 1.05kg each, so the pheasant biomass is about 41,000 tonnes. We have used estimates of population size and biomass in the intervening period to complete the curve in the graph. In September we estimate that birds are nearing full weight, so there are 41 million young adult pheasants that weigh 0.95kg and 2 million from the previous year that weigh 1.15kg. This gives us our estimated peak biomass of pheasants at 41,250 tonnes.

It appears that the estimate of pheasant biomass after their release in Blackburn and Gaston’s 2018 paper did not take account of the lower weight of birds when they are released or of post-release mortality. However, the paper also underestimated the number released, so these factors, combined with the revised adult pheasant weight of 1.15kg approximately balance out. This means that in September, after the pheasant releasing season, the total biomass of pheasants in Britain is calculated to be 1.63 times the total biomass of breeding birds in spring. We need to remember that this comparison uses a number for pheasants at the time of year when biomass is at its maximum, and a number for all other birds when the resident population is at a minimum.

Shooting season – November to February

During the shooting season, the mortality rate of pheasants caused both by shooting and other factors leads to a continued decline in numbers6. This is used in the graph above to calculate the decrease in numbers and biomass during that period. GWCT radio-tracking studies show that, typically, 16.5% of the pheasants released were still alive after shooting finished in February each year6,7. Based on this, 7.75 million of the year’s released pheasants are thought to remain. Adding a very small number from the previous release nearly 18 months prior, this can be rounded up to 8 million.

Spring post-shooting season

For the post-shooting season in spring, studies of survival in hen pheasants from early February until June found that around half die, mostly from predation7. In figure 1 we assume this trend continues into late summer and beyond. This approach suggests 4.5 million pheasants remaining in May, which roughly agrees with the 4.6 million latest census estimate of breeding pheasants8. There is a complication here because the census figure is based on surveys undertaken throughout the spring and it includes an unknown number of truly wild pheasants, but it is reassuring that the two numbers are very similar. So, in spring 4.5 million pheasants have a combined biomass of 5,175 tonnes which is about 20% of the total breeding population of birds in the UK1 (see box below). This is at the low end of the estimates given on More or Less.

Note that neither the figure for breeding pheasants nor for total breeding birds includes the young they produce. Studies have shown that nest success of released pheasants on UK shoots is particularly low, probably on average around 10%9. A series of unpublished GWCT radio-tracking studies suggest that the survival of hatched chicks is highly variable but also very low in most situations7. Overall, we estimate the number of chicks produced by the surviving released pheasants each year to be well below 0.5 million, which is less than the error in some of our other estimates and would not significantly alter the line in the graph. We do not have a figure for the overall breeding output of the total bird population.

Pheasant versus woodpigeon?

Pheasants are not the most abundant large bird in the UK in spring. The breeding adult population of woodpigeons is currently estimated to be 10.1 million6, slightly down on the previous estimate3. The mass of a woodpigeon is 450 grams according to the BTO and 480 grams in an earlier Gaston and Blackburn paper4. This gives a total woodpigeon biomass of between 4,550-4,850 tonnes (18-19.5% of total breeding bird biomass), about the same as pheasants in June.

Total number and biomass of breeding birds in the UK/Britain

Number

The estimated total number of pairs of breeding birds in spring in the UK from Blackburn and Gaston’s 2018 paper was 84 million3. This number is based on surveys undertaken in various previous years and uses estimates based on previous numbers. The survey timings vary with species, but typically would be in April to June. This number has just been updated using a similar approach, and for 2016 the total remained unchanged at 84 million breeding pairs8. In Britain alone the figure is 79 million. At this time in spring, after winter mortality and before birds produce young, the overall number of resident birds in the UK will be at its lowest point in the year.

Biomass

The estimate we have of the biomass of the total British (not UK) breeding bird population in spring is from the 2013 population estimates3,10 as used by Blackburn and Gaston and is 23,964 tonnes of birds1. We can assume this has changed very little since 2013, because the overall population estimate has not changed (note that the relative proportion of pheasants and some other larger birds such as woodpigeons has changed, but in differing directions so probably cancelling each other out). However because Blackburn and Gaston underestimated the biomass of the 4.4 million breeding pheasants in their paper (0.85kg per bird instead of 1.15kg) we can make an adjustment for that to give an overall biomass figure of British breeding birds of 25,284 tonnes. As before, at this point in the year the biomass of all birds will be much lower than later in the summer.

Discussion

These calculations show that, because of the huge variation in numbers and biomass of pheasants throughout the year, pheasant biomass is about 0.2 of the total British bird biomass in spring and 1.6-1.7 times the same spring estimate for all birds in the autumn. However, the yearly change in biomass for breeding birds is unknown; there are no estimates for after breeding, when biomass will be at its maximum. The comparison between spring numbers is valid, but comparing peak pheasant biomass in autumn with the lowest point of the year for resident breeding birds is not. For this, it would be useful to have an estimate for the numbers and biomass of the total breeding population of birds, including their young, later in the year.

However, this discussion raises a wider question: what is the underlying reason for comparing the biomass of released gamebirds to wild breeding birds in this way, and does it serve a purpose in giving us useful information? The aim is important; to contextualise the number of pheasants released and encourage the audience to think about the potential effect of pheasant release on the countryside. However, comparing biomass, particularly from different times of the year, does not in itself give a meaningful indication of their relative impacts.

In some respects, pheasants are similar to farmed birds such as ducks, chickens and turkeys, but the obvious differences mean it also wouldn’t be a helpful comparison. Pheasants and other released gamebirds sit between the two categories – being classed as livestock until they are released and then wild birds afterwards. Comparing the biomass of released pheasants to either group gives little information about the underlying question of the effects of released pheasants, potentially diverting attention away from this fundamentally important area.

Instead, it would be more informative to examine studies looking directly at the effect of pheasants on flora, fauna, local predators and so on. These studies have been reviewed by scientists from the University of Exeter and the GWCT in a research report for Natural England10, to be published in July, and a forthcoming review by the RSPB.

One of the main differences between released gamebirds and most wild birds is that the habitats pheasants use such as woodlands and game crops are managed and improved or created specifically for those releases. This management is widespread and usually benefits other wildlife. However, the presence of so many pheasants in woodland and elsewhere can have negative effects on those habitats and potentially the wildlife in them. This mixture of positive and negative effects of releasing is described in these reviews and will be considered in a separate What the Science Says briefing piece.

Donate and help us fight misinformation

References

- Blackburn, T.M. & Gaston, K.J. (2018). Abundance, biomass and energy use of native and alien breeding birds in Britain. Biological Invasions, 20:3563–3573.

- Aebischer, N.J. (2019). Fifty-year trends in UK hunting bags of birds and mammals, and calibrated estimation of national bag size, using GWCT’s National Gamebag Census. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 65:64 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344–019–1299–x.

- Musgrove, A., Aebischer, N.J., Eaton, M., Hearn, R., Newson, S., Noble, D., Parsons, M., Risely, K. & Stroud, D. (2013). Population estimates of birds in Great Britain and the United Kingdom. British Birds, 106:64–100.

- Gaston, K.J., Blackburn, T.M., Greenwood, J.J.D., Gregory, R.D., Quinn, R.M. & Lawton, J.H. (2000). Abundance-occupancy relationships. Journal of Applied Ecology, 37:39–59.

- Beer, J.V. (1995). Nutrient requirements of gamebirds. Recent Advances in Animal Nutrition: (eds. Cole, D.J.A. & Haresign, W.) Butterworth. London.

- Turner, C.V. (2007). The fate and management of pheasants (Phasianus colchicus) released in the UK. University of London.

- Sage, R.B., Turner, C. V., Woodburn, M.I.A., Hoodless, A.N., Draycott, R.A.H. & Sotherton, N.W. (2018). Predation of released pheasants Phasianus colchicus on lowland farmland in the UK and the effect of predator control. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 64:14.

- Woodward, I., Aebischer, N., Burnell, D., Eaton, M., Frost, T., Hall, C., Stroud, D. & Noble, D. (2020). Population estimates of birds in Great Britain and the United Kingdom. British Birds, 106:64–100.

- Draycott, R.A.H., Hoodless, A.N., Woodburn, M.I.A. & Sage, R.B. (2008). Nest predation of Common Pheasants Phasianus colchicus. Ibis, 150:37–44.

- Madden, J. & Sage, R. (2020). Ecological Consequences of Gamebird Releasing and Management on Lowland Shoots in England. In press.